Opening Night

Gerald R. Ford Amphitheater

Whenever I’m about to view a work by one of the great choreographers of the 20th century for the first time, I like to do a little digging. Why was this piece of dance created? What did it mean in its time, and how can we relate to it now? After seeing that the Martha Graham Dance Company would be performing Graham’s 1947 Errand into the Maze at the Vail Dance Festival this summer, I got out my metaphorical shovel and started to dig. You could even say I went on my own errand…into the labyrinth of books, articles, and resources housed in the New York Public Library. What follows is everything might want to know before your first viewing of this masterwork.

Martha Graham (1894-1991) drew inspiration for her works from a wide variety of literary sources such as poetry, Greek mythology, American history, folklore, rituals, and ceremonies.(1) The structure and setting of a dance might be based on an established story, but into that, Graham would inject her own ideas of the characters’ struggles and emotions. In the case of Errand into the Maze, there are two pieces of literature that Graham used as a framework.

The first source was a poem titled “Dance Piece” by her friend Ben Belitt.(2) As friends, they corresponded for years. In fact, Belitt dedicated “Dance Piece” to Graham when he wrote it. Surprisingly, it was not until years later that Graham read his poem when he sent her a copy of it in a letter. Upon reading it, she was captivated by the opening line, “On an errand into the maze…” To her, the word errand “involves a choice of will and into an area or element of peril […] from which the participant fully intended to return” (3)… She tucked the poem in the mirror of her dressing table.(4) The idea for a new work was taking root.

Errand into the Maze became the title for her next work, but what errand would the lead dancer go on, and through what maze would she move? In 1946, Graham began to find in Greek mythology “the primary myths of her own being and experience”. (5) Eventually, eleven of her works would take shape around Greek myths. When dance writer Walter Terry questioned Graham on her habit of using Greek mythology for the core of her heroines, she answered: “There seems to be a way of going through—in Greek literature and Greek history—all of the anguish, all of the terror, all of the evil and arriving someplace. In other words, it is the instant that we all look for, the catharsis through the tragic happenings” (6)

For Errand, the source material was the myth of Theseus and Ariadne. To understand the depth of Graham’s storytelling onstage, I found it helpful to understand the nuances of this myth. I’ve summarized it as briefly as possible while still including details pertinent to the dance work:

In Greek mythology, King Minos, the ruler of Crete was married to Pasiphaë. Pasiphaë became enamored with a bull that had been meant to be a sacrifice to Poseidon. Rather than sacrificing the bull, King Minos sacrificed a different animal. Poseidon, angry that he had not received the proper sacrifice, turned the bull into a menacing beast. Still taken by the bull, Pasiphaë and the bull united and the offspring that was created was the Minotaur—half man, half bull. Worried by this new creature, King Minos ordered that a palace be built with complex corridors and rooms, to keep the Minotaur trapped inside. The name of the palace was Labyrinth. With no natural source of sustenance, King Minos demanded that 7 men and 7 women be sent to the Minotaur as sacrifices at regular intervals. No one had ever been able to escape because they would be lost trying to find their way out.

On one occasion, Theseus volunteered to go as a sacrifice and slay the Minotaur, so he was sent to the island of Crete. Upon arriving, Theseus met Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos and Pasiphaë, who fell in love with him. To help him escape the Labyrinth alive, Ariadne gave him a ball of string to tie to the entrance and unravel as he traveled through the halls. This way, if his mission was successful he would be able to retrace his steps to escape by following the string.(7)

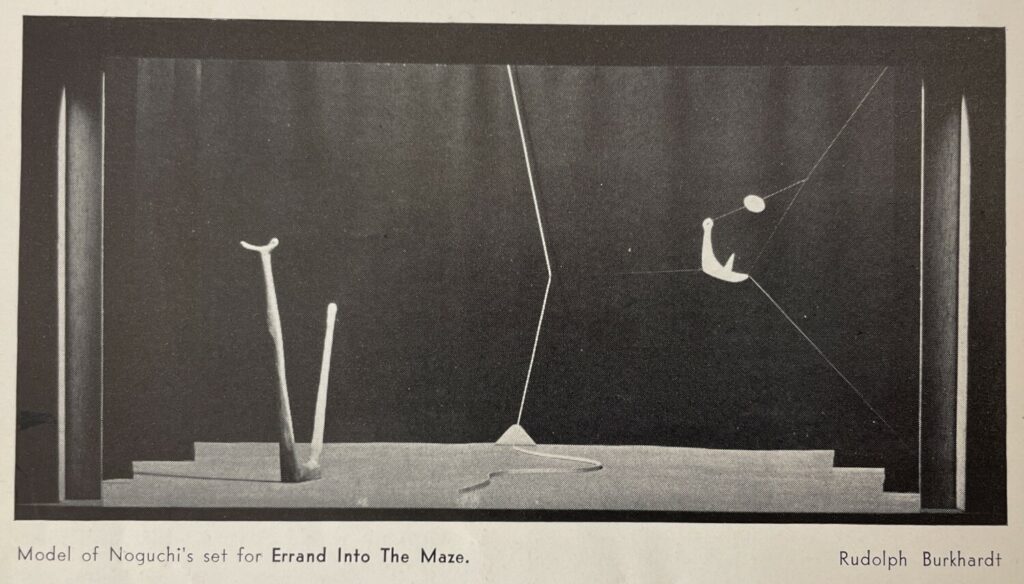

Errand features just two dancers; the story was reimagined to feature Ariadne as the heroine who enters the Labyrinth and slays the Minotaur. The set includes a string zig-zagging across the stage to the base of a large 2-pronged sculpture that resembles the forked base of a tree. (Fig. 1) As Ariadne embarks on her journey, she is thwarted at first by the appearance of the Minotaur.

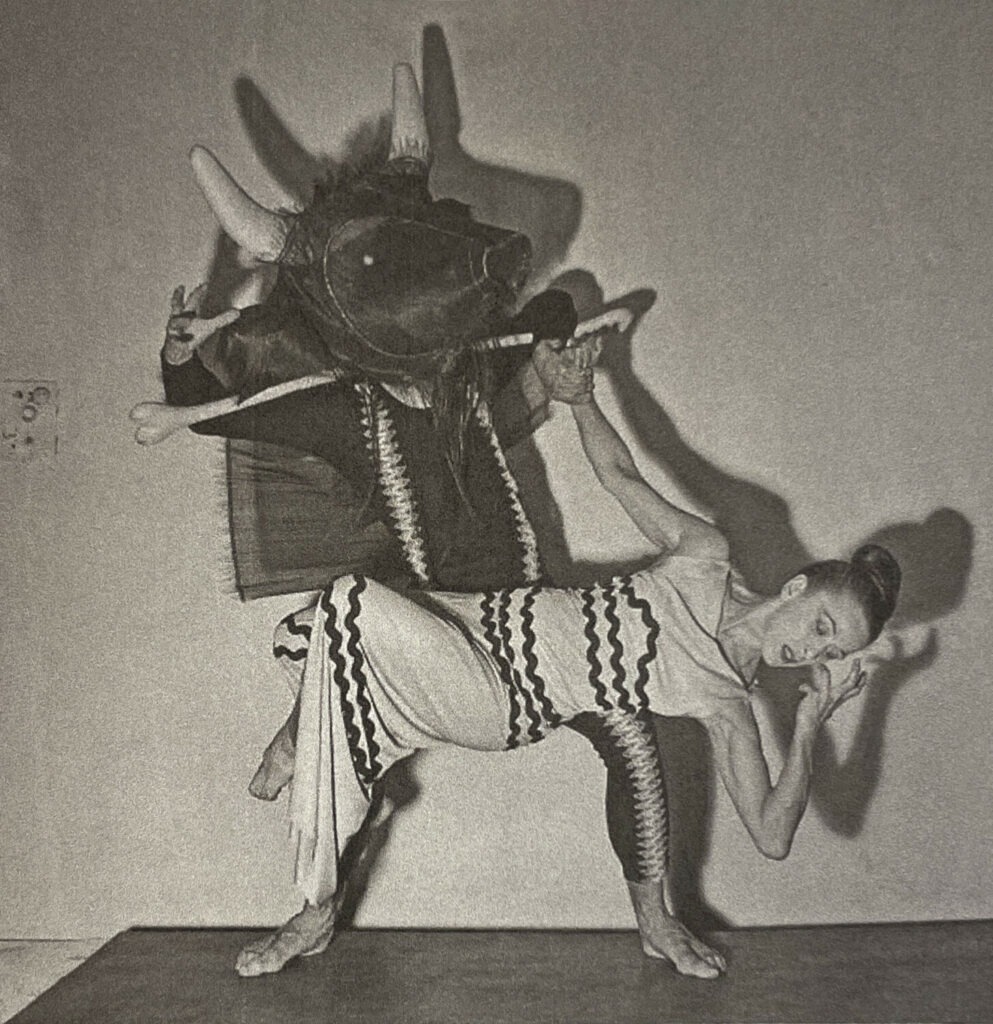

Although he appears menacing, he is more of an intimidating presence than a physically dangerous one. With his arms entwined around the yoke on his back, he is prevented from inflicting much harm. (Fig. 2) Graham said, “This dance has a special significance for me because it expresses the conquering of fear in my life, fear of the unknown, fear of something not quite recognizable.” (8) In a 1954 program note she wrote, “the heroine enters the maze of her own heart, goes along the frail thread of her courage to find the fear which lurks like a Monster, a Minotaur, within her. She encounters it, conquers it, and emerges to freedom.”(9)

Although he appears menacing, he is more of an intimidating presence than a physically dangerous one. With his arms entwined around the yoke on his back, he is prevented from inflicting much harm. (Fig. 2) Graham said, “This dance has a special significance for me because it expresses the conquering of fear in my life, fear of the unknown, fear of something not quite recognizable.” (8) In a 1954 program note she wrote, “the heroine enters the maze of her own heart, goes along the frail thread of her courage to find the fear which lurks like a Monster, a Minotaur, within her. She encounters it, conquers it, and emerges to freedom.”(9)

This triumphant “emergence” takes place when the heroine steps through the literal or figurative trunk-like set piece (Fig. 3) which has also been described as a model of a woman’s pelvic bone.(10) This symbol allows the audience to interpret Ariadne’s exit from the maze as a rebirth; coming through the experience of conquering her fear a wiser and stronger person. In recent years, the Graham company has performed this masterwork both with and without the set as it will be performed in Vail, each adding a visual aspect that both tells the story and adds unique insight into it.

It is important to note that the female dancer is not a passive recipient of her fate. She is the catalyst for all action. First of all, the errand is a choice, she is not forced on such a mission but chooses to go. When you consider that the Minotaur is Ariadne’s half-brother (sharing the same mother), you realize that he is quite literally a frightening part of herself that she chooses to face. The other strong choice that the heroine makes is her use of the thread string. By approaching her mission with an analytical plan she is able to focus on the test at hand—facing “fear”—without the distracting worry of how she might navigate out of the maze if and when she completes her task. This methodical approach establishes that the heroine is the executor of her own fate.

The effect of Errand into the Maze on audiences has not been stunted by being tied to a time and place that could become dusty and outdated. Rather its story of a universal peril of the human condition has given it longevity. This is why, after 76 years, audiences still feel Errand is “of particular appropriateness in these times when fear attacks us all.”( 11) And as Sabin wrote in 1963, “We do not see [Graham’s works] through a historical haze; we live and breathe and suffer with them.” (12) “For the spectator who fully participates, her plays are ritualistic experiences.” (13)

Notes:

Figure 1 Burkhart, Rudolf. Model of Noguchi’s Set for Errand into the Maze. 1947. Photograph. The Noguchi Museum.

Figure 2 Fehl, Fred. “The Struggle of a Woman with Her Creature of Fear, Danced by Martha Graham and Mark Ryder in ‘Errand into the Maze’.” Dance Magazine 22, no. 4 (1948): 12. Accessed June 29, 2023 via New York Public Library Dance Collection.

Figure 3 Errand into the Maze. 1947. Photograph. Pictorial Press, London, February 28, 1947.

Figure 4 Ochs, Michael. Martha Graham’s “Errand into the Maze”. 1947. Photograph. Getty Images, December 30, 1947.